Images Stuart Napier, text Genevieve Carbonatto

A 24 year old presents to the emergency department with right upper quadrant pain after playing rugby. He tripped, landing on his right elbow jamming into his right upper quadrant. He was immediately winded and felt right upper abdominal pain. On waking the next morning he had severe right upper quadrant/flank pain and macroscopic haematuria with no clots.

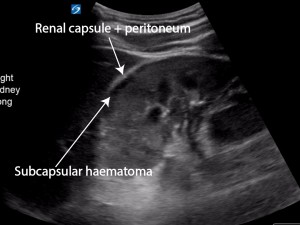

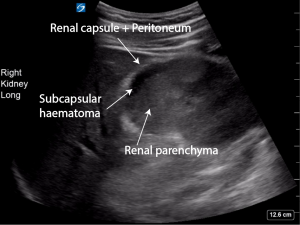

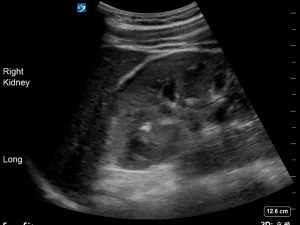

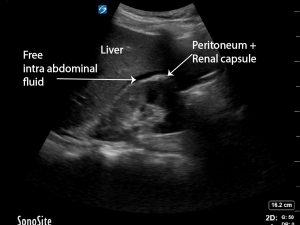

On examination he had marked tenderness of his right flank. A point of care ultrasound is performed. This is his right kidney

There is a subcapsular haematoma visible on ultrasound. It is not entirely anechoic. There are some faint hyperechoic strands visible within the subcapsular haematoma as the haematoma has had time to organise over the time of the initial injury. Fresh blood will appear completely anechoic. Older blood will be heterogeneous in echogenicity and at times frankly hyperechoic.

There is good perfusion of the kidney.

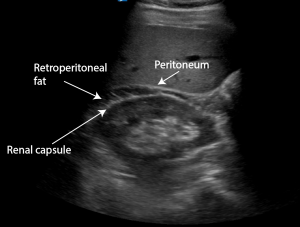

How do we know this is not intraabdominal free fluid or retroperitoneal fat (the double line sign)?

Free fluid lies between the liver margin and the peritoneum. The liver margin is not hyperechoic. The peritoneum is. If there is no retroperitoneal fat visible on ultrasound, the hyperechoic renal capsule is indistinguishable from the peritoneum.

Retroperitoneal fat lies between the renal capsule (hyperechoic) and the peritoneum (hyperechoic). It can be almost anechoic, however often there are echos within it. The double line sign refers to the anechoic/hypoechoic fat seen as sandwiched between the 2 hyperechoic lines.

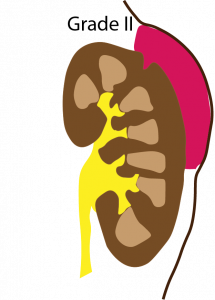

The patient had a CT IVP which showed a small focal cortical laceration in the right renal upper pole with no evidence of urine extravasation consistent with an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Grade II renal injury. His haemoglobin was 160 and his creatinine normal. The patient was admitted for observation and discharged 48 hours later.

Discussion (1,2,3)

- Incidence of renal injury in trauma : 1-5%

- May be due to blunt or penetrating injuries . Blunt injuries are overwhelmingly ( >94%) the cause of renal injuries and are usually secondary to high energy motor vehicle accidents (MVA), falls from a height or contact sports. Stabbings are the most common cause of renal injuries in Australia (4), while gunshot wounds are more common in the United States.

Scoring scale of renal injuries

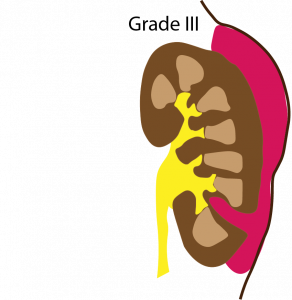

The injury severity injury scale for renal injuries has been developed by the American Association for the Injury of Trauma. Renal injuries have been classified into five groups.

- Grade I : Contusion or nonexpanding subcapsular haematoma without parenchymal laceration

- Grade II: Non expanding perirenal haematoma or laceration < 1cm deep without urinary extravasation

- Grade III: Laceration > 1cm deep without urinary extravasation

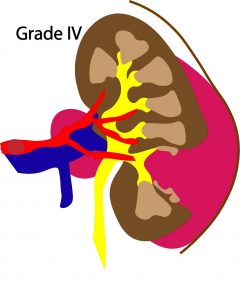

- Grade IV: Laceration extending through the renal cortex into the collecting system or segmental renal artery or vein injury with contained haemorrhage or partial vessel laceration or vessel thrombosis

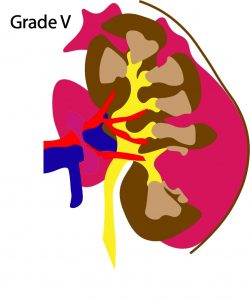

- Grade V : Shattered kidney or renal pedicle injury/avulsion of renal hilum

Management

- Resuscitation if haemodynamically unstable. Haemodynamic instability can be due to severe renal injury but often is due to associated injuries in the context of trauma (liver/ splenic/ bowel/orthopaedic including lumbar verterbral or transverse verterbral fractures)

- An EFAST scan is performed to look for intraperitoneal blood, pericardial effusions and pneumothorax in the context of trauma . The kidney is further assessed by checking the renal function (creatinine).

- Management of haemodynamically stable Grade I to IV injuries is usually conservative. This does not apply for Grade IV unstable vascular injuries which may need intervention.

- Grade V haemodynamically stable patients may require surgical intervention, usually nephrectomy.

- Ureteropelvic junction injuries rarely heal spontaneously and therefore best managed by surgical repair at the time of injury as complications such as persistent urinary leak, urinoma formation , ileus and infection may arise

- In the haemodynamically unstable patient laparotomy and exploration is usually due to concomitant injuries (spleen, liver, orthopaedic). Indication for renal exploration include life threatening haemorrhage , renal pedicle avulsion or a pulsatile /expanding retroperitoneal haematoma at the time of laparotomy.

- Arterial embolization is usually performed first when there is active extravasation of iv contrast and the patient does not require an urgent laparatomy to avoid surgery which often leads to nephrectomy

- Urinary extravasation in itself does not demand surgical exploration. Extravasation confirms the diagnosis of major renal injury. Urinary extravasation will generally heal spontaneously in the majority (87% in one study) of patients. Complications of urinary extravasation include a persistent leak, sepsis or the formation of a urinoma

Role of imaging

- Indication for imaging include hypotension, blunt trauma and gross haematuria

- Gross haematuria is the most reliable indicator of serious renal injury

- The degree of haematuria however does not always correlate with the degree of renal injury as Grade V renal injuries with renal pedicle avulsion or acute thrombosis of segmental renal arteries can occur in the absence of haematuria.

CT scan:

- CT scan is the gold standard to grade the severity of the renal injury.

- It is sensitive and specific in identifying parenchymal lacerations, urinary extravasations, delineating segmental parenchymal infarcts and for determining the size and location of the surrounding retroperitoneal haematoma and /or associated intra abdominal injuries (5)

Point of care ultrasound:

- Identifies haemoperitoneum (> 90% sensitive)

- Operator dependent if localising a subcapsular or perinephric haematoma and especially if localising parenchymal haematomas which are more difficult to identify. Parenchymal haematomas present as areas of mixed echogenicity. Colour Doppler may identify perfusion defects in the damaged parenchyma.

- Ultrasound is unable to distinguish fresh blood from extravasated urine.

- Ultrasound cannot distinguish between vascular pedicle injuries and segmental infarcts.

IVP

- Useful in establishing the presence of functioning kidneys and the presence and extent of urinary extravasation

- Unable to define the full extent of the renal injury as it is not sensitive in picking up parenchymal injuries.

Teaching point: Ultrasound is not the best modality to identify renal injuries. It is however a very useful tool in identifying intraabdominal fluid. It is important to recognise the difference between intra abdominal fluid, retroperitoneal fat and subcapsular haematomas when scanning through Morison’s pouch.

References

- Cureus. 2018 Jan; 10(1): e2113. Isolated Renal Laceration on Point-of-care Ultrasound Madeline M Grade,corresponding author1 Cori Poffenberger,1 and Viveta Lobo

- Rev Urol. 2011; 13(2): 65–72. Contemporary Management of Renal Trauma Jennifer J Shoobridge, BMedSci, MBBS, MPH,1 Niall M Corcoran, PhD, FRACS(Urol),1,2 Katherine A Martin,3 Jim Koukounaras, BMBS, FRANZCR,4 Peter L Royce, MBBS, FRACS(Urol), FACS,1 and Matthew F Bultitude, MBBS, MRCS, MSc, FRCS(Urol)

- World J Radiol. 2013 Aug 28; 5(8): 275–284.Imaging in renal traumaMadhukar Dayal, Shivanand Gamanagatti

- Clin Radiol. 2008;63:1361–1371Urological injuries following trauma. Bent C, Iyngkaran T, Power N, et al.

- Renal Trauma: A Practical Guide to Evaluationand Management Steven B. Brandes, MD and Jack W. McAninch, MD The Department of Urology, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, CA

- JPMA Role of Imaging in the evaluation of Renal TraumaM. H. Ather, M.A. Noor

Great case and images