Images and text Genevieve Carbonatto

History: A young 32 year old lady presents to the Emergency Department SOB (short of breath). She is 4 weeks postpartum and was well during her pregnancy. She did not suffer from pre eclampsia during or just after her pregnancy. The baby was born by Caesarian section. She descibes being perfectly well until 24 hours prior to admission. She has noticed that she is SOB on exertion and SOB especially when she lies flat. She has mild chest wall tightness which improves when she sits up

On examination: She is lying comfortably in bed with no increase in work of breathing at rest. Her HR is 100/minute, BP 110/80, JVP 3cm. No murmers audible. She has a occasional bibasal crepitations on chest examination. No ankle oedema.

This is right anterior chest lung ultrasound

This is her left anterior chest ultrasound. More than 2 B lines between 2 intercostal spaces indicating an interstitial syndrome

More than 2 B lines between 2 intercostal spaces indicating an interstitial syndrome

ECHO PLAX

Poor LV contraction, RV not dilated

ECHO PSAX

Global LV dysfunction – poor contraction, RV not dilated, no evidence of significant increased RV pressure causing flattening of the IVS

ECHO 4 chamber view

Poor LV contraction LA not dilated, poor visualisation of RV lateral wall

From this study it is clear that this patient is suffering from a nondilated cardiomyopathy causing pulmonary oedema. The interstitial syndrome in the context of the ECHO findings is most likely due to pulmonary oedema

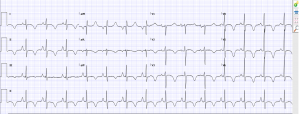

ECG

ECG shows a sinus rythm with widespread widespread T wave inversion.

Discussion

SOB in the post partum patient requires particular attention. The differential diagnoses to be considered include pulmonary embolus, peripartum cardiomyopathy or pulmonary oedema from preeclampsia. It may be functional from anaemia post delivery. The risk for pulmonary embolism is highest in the first few weeks after delivery and then drops steadily through week 12, the highest riskbeing in the first 6 post partum weeks. The incidence of PE was found to be 13 per 10,000 deliveries (4) in a Swedish study. The incidence of peripartum cardiomyopathy varies worldwide being higher in developing countries – up to 1% in Nigeria for example to 1:3,000–4,000 deliveries in the States (5). Estimated rates of acute pulmonary oedema in postpartum preeclampsia vary from as low as 0.08% to as high as 0.5% (6)

Definition of peripartum cardiomyopathy

‘Peripartum cardiomyopathy is an idiopathic cardiomyopathy presenting with HF secondary to left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction towards the end of pregnancy or in the months following delivery, where no other cause of HF is found.” (1)

Criteria for peripartum cardiomyopathy

- development of cardiac failure in the last month of pregnancy or within 5 months of delivery

- absence of an identifiable cause for the cardiac failure other than pregnancy

- absence of recognisable heart disease before the last month of pregnancy

- left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <45% by echocardiography, fractional shortening <30%, or both.

PPCM is a diagnosis of exclusion

Incidence

Rare 1/4000 births approx but varies geographically

Risk factors

The strongest risk factor for PPCM appears to be African-American ethnicity (OR 15.7; CI 3.5–70.6) (5). Other reported risk factors include age, pregnancy-induced hypertension or preeclampsia, multiparity, multiple gestations, obesity, chronic hypertension, and the prolonged use of tocolytics

Pathophysiology

Several mechanisms have been proposed

- Prolactin related : increased cleavage of prolactin into antiangiogenic and proapoptic isoforms

- Autoimmune mechanisms

- Inflammatory mechanisms

- Viral infection

- Genetic Susceptibility

Clinical presentation

- Signs of heart failure: ankle oedema, shortness of breath on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea

- Abdominal discomfort, palpitations, dizziness, chest pain

- 78% present in the first 4 months after delivery

- 9% in the last month of pregnancy

- LV thrombi (10 -17% of patients) with patients presenting with cerebral or coronary emboli

- Non specific ECG changes. Sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and ventricular tachycardia.

ECHO

- Important to rule out other causes of heart failure.

- If the LVEF >30% at diagnosis, return to normal EF is likely

- The left ventricle is not always dilated. A left ventricular end-systolic diameter of ≤ 5.5 cm predicts good recovery of left ventricle function.

Treatment

- Similar to patients with non ischaemic cardiomyopathy from other causes includes oxygen: fluid restriction, loop-diuretics and/or other diuretics, nitrates, and hydralazine (safe to use during pregnancy), especially for hypertension.

- Anticoagulation due to high incidence of LV thrombi

- If a patient has persistently depressed LV dysfunction 6 months following presentation despite optimal medical therapy, implantation of an ICD is advised.

Prognosis

- Good prognosis if : LV EDD < 5.5 cm and LVEF > 30 -35% at the time of diagnosis, absence of troponin leak or LV thrombus

- Prognosis is variable however. Despite the strong association between LVEF at time of diagnosis and rate of recovery, 70% of patients with LVEF of 10–19% and 87% of patients with LVEF 20–29% recover almost beyond the “device threshold” for an ICD at ≥6 months (3)

Teaching point: The specific differential diagnosis of SOB in the peripartum patient can be refined at the bedside in the Emergency Department with ultrasound. Examination of the lung for pulmonary oedema, examination of the heart for cardiomyopathy or signs of pulmonaty embolus will quickly help in establishing the diagnosis along with clinical findings, ECG and basic blood tests.

References

- Peripartum cardiomyopathy: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Office of Rare Diseases (National Institutes of Health) workshop recommendations and review.Pearson GD, Veille JC, Rahimtoola S, Hsia J, Oakley CM, Hosenpud JD, Ansari A, Baughman KL

JAMA. 2000 Mar 1; 283(9):1183-8. - Elkayam U, Akhter MW, Singh H, Khan S, Bitar F, Hameed A, et al. Pregnancy-associated cardiomyopathy: clinical characteristics and a comparison between early and late presentation. Circulation. 2005 Apr 26. 111(16):2050-5.

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy: A Contemporary ReviewTina Shah, M.D.,a Sameer Ather, M.D., Ph.D.,a Chirag Bavishi, M.D., M.P.H.,b Arvind Bambhroliya, M.D., M.P.H.,a Tony Ma, M.D.,a,c and Biykem Bozkurt, M.D., Ph.D.a,c. Methodist Dubakey cardiovasc J 2013 Jan-Mar; 9(1): 38–43

- Lindqvist P, Dahlbäck B, Marsál K. Thrombotic risk during pregnancy: a population study. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:595–9.

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy :A Review Anirban Bhattacharyya, MD, Sukhdeep Singh Basra, MD, MPH, Priyanka Sen, BS, and Biswajit Kar, MD

- Review Article Acute pulmonary oedema in pregnant women A. T. Dennis, C. B. Solnordal. Anaesthesia march 15 2012